In my teens I was trained in a form of evangelism called Two Ways to Live. There was a whole package of materials – a workbook, posters, pamphlets to hand out, and we were encouraged to learn how to draw diagrams and learn bible verses to go with them. The idea was that, if someone asked how they could become a Christian, you would be ready to explain it to them. I didn’t know at the time that the package was designed by Philip Jensen, who went on to become Dean of the Anglican Cathedral in Sydney, nor that it presented a particular view of the Christian faith grounded in the work of Swiss Reformer John Calvin. It was presented as though it was an uncontroversial, universally accepted narrative to explain faith in Jesus Christ.

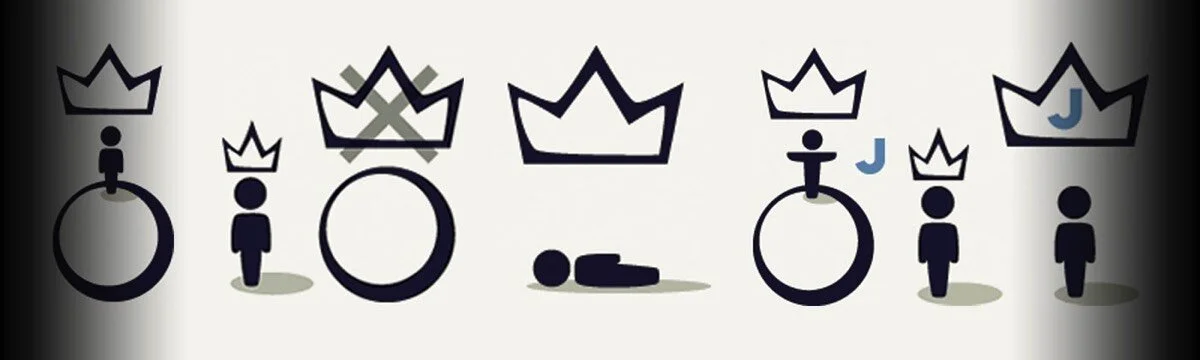

It begins by explaining that God made the world and is in charge of the world. Human beings have rejected God’s authority, and, as such, deserve punishment. God, however, has provided us with an alternative. If we believe and accept that Jesus received the punishment on our behalf, and acknowledge that God is truly the boss of the world, then we don’t have to experience death and divine punishment, and instead we can live now and in the next life in relationship with God.

You might recognise this account of the Christian faith. It was made popular by Billy Graham, for example, and it’s the kind of message that has been preached at evangelistic rallies and youth events for decades. It’s an understanding of God and salvation called ‘penal substitutionary atonement’ and it is currently the most dominant narrative of the Christian faith in the world. I’m not here today to critique penal substitutionary atonement in its entirety . I’m talking to you because I want specifically for us to consider where this narrative, where this explanation of ‘good news’ begins. It starts with two things – Creation and Fall. God made the world, and it was good. Humanity have rejected God’s authority, and are, as a result, bad. These are really important theological points. They come up again and again in our scriptures and our liturgy. Creation and Fall are absolutely concepts that we need to understand.

But if someone says to me ‘How can I become a Christian?’ or ‘what does it mean to become a Christian?’ or even something more vague ‘Why do you see the world differently to me?’ or ‘Why do you keep going to that weird church?’ –wouldn’t I start first and foremost by talking about Jesus? Wouldn’t I talk about Jesus’ character and stories? Wouldn’t I talk about his disgusting death and remarkable return to life? Wouldn’t I talk about the way he is present today – in the poor, in the church and in the sacraments? And wouldn’t I talk about how I am utterly intoxicated by the character of Jesus, how he inspires me, he empowers me, he sustains me – how Jesus walks alongside me, challenges me, surprises me? Why would I start with a series of intellectual dot points about Creation and Fall, instead of with an actual flesh and blood person who is humanity’s gateway to divine?

In my experience, once a person is gripped by Jesus – once they are drawn into his life, they ‘get’ sin very quickly. ‘Ooooh!’ they say ‘this is what full humanity is meant to be, and I see how I have been falling short’. And they get Creation without any trouble at all ‘Oooooh! If Jesus is like a window that shows us God, it is blindingly evident that God made and loves the world’. Even a complex concept like the atonement doesn’t need a huge amount of explanation – because the Jesus-intoxicated person has already experienced how the barrier between God and the world is bridged by Jesus. Even the doctrine of the Trinity doesn’t need some lengthy, verbose dissertation. It is the lived experience rather than the learned dogma.

I guess what I’m saying is this: the big theological and doctrinal ideas are absolutely important. But the starting point is the person of Jesus. It’s as though he is the hub, and all these other important points about the bible and soteriology and eschatology and prayer and mission, emanate from the one centre. We don’t need to start somewhere over here by talking about creation and sin, nor in some other place talking about the Enneagram or social justice – we begin by talking about Jesus, the person, who is the embodiment of a personal God who is overflowing with love for people like us.

As we’ve been reading through 1 John, this circular teaching document from a character who calls himself The Elder, we’ve seen that the community is divided. There seems to be a group who left because they believe that Jesus was born of water only, not water and blood. Let me explain. They seemed to believe that Jesus was not actually human, but only looked that way. He was kind of dressed up in a human body (like the Greek and Roman gods were sometimes) but he didn’t actually suffer and die like an ordinary human would.

Now, I’m going to let you in on something here – lots of people think that today, and throughout history. It’s a heresy called Docetism, but there are plenty of people who, for all practical purposes, believe and teach that Jesus wasn’t really a human being, but was a kind of supernatural ghosty guru who just looked like a human being. They imagine that Jesus could read minds and teleport and that Jesus had foreknowledge of all the Pilate and Herod and getting murdered thing - and in fact planned for it to happen that way.

The trouble with this heresy - despite being initially attractive and despite it providing neat answers to some questions – is that Jesus is not attractive. If Jesus is angel superhero, then why is anything he said or did remarkable? And if he didn’t actually suffer or die, but only appeared to, why would that mean anything or make a difference to my life?

The fully human, fully divine Jesus is a paradox, sure, but the historical person whom we meet in the scriptures and the still-living person we meet in the most unexpected of places – that’s the one who actually makes people change their lives, give up the toxic habits and selfish behaviours, that’s the one who causes people to sacrifice and self-empty and let the new life in. It is the living Jesus Christ who transforms lives and communities, both in first century Palestine and Syria, and in the 21st Century in the Shire of Mundaring.

The Elder, writing to a new church, is trying (in his wordy and convoluted way) to keep their focus on Jesus Christ who was both fully human and fully God. We know, he will say, that the whole world lies under the power of the evil one. But God gave us eternal life. This eternal life is not about living forever like one of the immortals. It is a quality of life, a life lived in deep connection with God. To live this life means to be love others sacrificially and generously now and to know that love more fully in the world to come.

Christ is Risen, Alleluia, Alleluia!