The Parable of the Three Portfolio Managers

Matthew 25:14-30

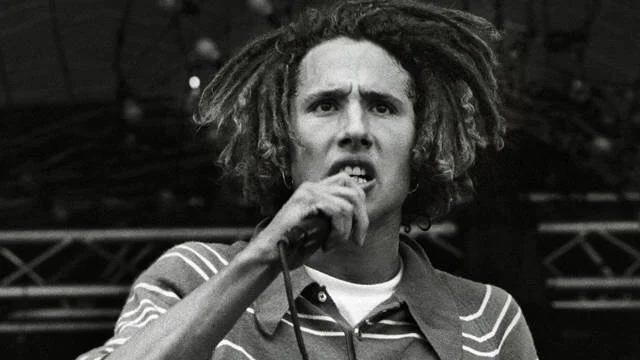

Last Saturday, footage began to circulate of Trump supporters in Philadelphia waving Trump flags and dancing to Killing in the Name, the iconic song by rock band Rage Against the Machine. For those who are not across music that was hip with the kids 27 years ago, Rage Against The Machine stands in the long tradition of protest music. Killing in the Name is their protest against racism in police forces and the military-industrial complex. It was inspired by the murder of Rodney King in Los Angeles. ‘Some of those that work forces are the same that burn crosses’ they sang in protest . When he saw the footage of the Trump Supporters dancing to the song, guitarist Tom Morello had a characteristically terse response: ‘Not exactly what we had in mind’.

This appropriation of content from its original context is not at all uncommon. Sure, it’s amazing that a song about how Black Lives Matter was appropriated by Trump supporters who strongly assert the opposite. But it’s also amazing that William Blake’s poem about radical revolution was appropriated as a hymn, and now Jerusalem is routinely and lustily sung in posh private schools and at rugby games.

And the parable of the Talents? I can’t tell you how many times I’ve heard it appropriated as an endorsement for sound financial management. Perhaps you have as well. The first two slaves, who made money for their owner, are held up as an example of prudent financial planning. But the third (who was so stupid he didn’t even put the money in the bank to earn interest) is portrayed as a poor role model. In English-speaking contexts, because the Greek word talanton sounds a bit like talents, the story has been appropriated to be about what you do with the gifts, resources and talents God gives you. ‘Don’t bury your talents in the ground, invest them so that you get more’. Or something. Complete nonsense.

Now, we need to be clear too that the author of Matthew’s gospel has appropriated the parable for his own literary purposes. In the place we have reached in Matthew’s gospel today, it is nearly the end of the day on Monday in Holy Week at the temple in Jerusalem. The previous day, Jesus has entered Jerusalem riding on a donkey, like the promised messiah. He has driven out the money changers and overturned the tables in the temple precinct. He’s ‘set up shop’ and is making everyone nervous and uncomfortable. He’s telling stories and teaching and having arguments with temple officials and experts. He moves out in front of the temple precinct and declares that the temple will be destroyed. His session is reaching a climax, and he begins to talk about the coming tribulation, the great clean up of the world. There will be great sufferings and persecutions. The Son of Man will return to set the world to rights. Then he concludes with three parables – the Ten Bridesmaids which we heard last week, the large sums of money which we heard today, and the sheep and the goats which we will hear on Christ The King Sunday next week. After the sheep and the goats, Matthew begins the passion narrative – the plot to murder Jesus and the events that lead to his execution. For Matthew, the intent of these three parables is crystal clear. Be alert. The end is nigh. Don’t be like the foolish bridesmaids, nor like the foolish servant, nor like the goats. It is undeniable that the author’s intent is to, quite literally, ‘put the fear of God’ into the listeners. Their conduct, their purity, their commitment and their wisdom must be unimpeachable when Christ returns in glory to judge the world. This the author’s primary concern.

So the literary context – the placement of this parable in Matthew’s gospel – is on Monday in Holy Week, standing out front of the temple precinct, at the climax of Jesus’ last ‘campaign speech’. The historical context of the author/s and listeners, is in the late first century in Antioch, after the Temple has been destroyed and during a period of significant conflict and persecution between Christ-followers and local synagogues, and between Jews, Christ-followers and the Roman imperial machine. But there’s another context that must be considered, and that this the context in which the historical Jesus told this story (presumably dozens or hundreds of times) to his followers in early first century Palestine.

I’ve said this a hundred times, but I’ll say it again for good measure – we should never assume that the powerful, rich, male landowner in a parable is equivalent to God. Why would we? The slave describes the landowner as ‘harsh man, reaping where you did not sow, and gathering where you did not scatter seed’. Is that how we or our Jewish friends understand God? Absolutely not.

So. Let’s agree that the landowner in the story is… a landowner. A fiendishly wealthy landowner. An obscenely rich person. He is going travelling, and he does not give a gift to each of his slaves. No. He entrusts each of three slaves with work to do while he is away. To the first he gives $4.5 million. To the second he gives $1.7 million. To the last he gives $900,000. This is not pocket money. This is serious investment capital. These slaves, who are clearly skilled and senior in their roles, are effectively brokers for the rich man. Their job is to deploy the money and earn a profit.

Now, let’s be clear. A rich landowner like this can only be a Roman citizen. The Empire had bought up vast tracts of land, and absentee landowners were very common. The local people, who had previously owned and farmed the land for themselves, became tenant farmers, making money for a foreigner. The hearers of Jesus’ story knew this situation extremely well. Instead of building up a sustainable local economy, with wealth and prosperity distributed amongst the local community, the profits went offshore and built up the wealth of an already rich family.

Of course, this would never happen today.

The first two slaves in the story know which side their bread is buttered. They take the megabucks and they put them to work. This doesn’t happen quickly – you can’t double an investment in a few months. But over the course of years, while the landowner is presumably at his villa in Naples or something, they pay as little as possible for labour and seed and land, and sell crops and livestock for the maximum profit. Along the way, no doubt, they’ve made a margin for themselves. This is just business, right? You’ve probably been in the same position, working to make your boss look good, and ensuring that the ultimate owners of a business clear a profit. In fact, most of us are bosses as well, one way or another, as our superannuation funds own shares in businesses which need to make money so we can have income in retirement.

But the third slave removes himself from the system. It is an audacious step to take. The listeners of Jesus would have filled in the gaps. Here’s this bloke with $900K from his boss, and for years on end he is doing nothing with it. No wages, no purchases. Perhaps they assumed he’d passed it on to a third party to do the work for him – the landowner suggests at least he could have given it to the money changers, maybe those at the Temple whose tables Jesus has just overturned? But no, he has buried it. Thirty kilograms of silver, in the ground. When the landowner returns, he just digs it up and hands it back. It’s actually quite comical. Imagine the sketch comedy where the first two slaves majestically reveal their vast piles of silver, while the third dusts the sand off a bag he’s just dug up from the backyard!

Then the slave names the reality of the landowner. He is harsh. And he is no farmer. He makes money off land where has done zero work. The landowner calls the slaved ‘wicked and lazy’ but the slave has got in first. The landowner is a bloated dilettante, enriching himself off the sweat of the workers. He doesn’t get his hands dirty. He relies on others to toil and sacrifice so that he can benefit.

Of course, this would never happen today either.

The defiance of this scene is extraordinary. ‘Here, you lazy, exploitative bastard – you get nothing from me.’

Imagine this story circulating throughout the Roman province of Palestina, once the proud nations of Judah and Israel. Imagine this subversive tale being told and retold, as listeners marvelled at the audacity of the third servant’s passive resistance. Imagine, perhaps, a few of the workers taking it seriously, and challenging the authority of their absentee landlords with a ‘go slow’ or a ‘work to rule’. Imagine how Jesus as the source of this dangerous story would have been the subject of suspicion and condemnation, both from those with power, and from those who didn’t want to upset those with power.

So, you see, the appropriation of this Parable of the Three Portfolio Managers as a lesson in obedience and financial responsibility was not accidental. It is so much safer to frame the story as a tale of prudent business practices because that won’t threaten the neo-liberal narrative of personal advancement through diligence and loyalty. But when we read the text that is actually there, not the text as we would prefer to read it, we read a story of defiance and truth-telling, the exposé of a cruel and exploitative master and the nonviolent resistance of an ordinary person. And the outcome is all too familiar – the rich get richer and the poor get poorer, and the prophet gets cast out.

The reality for me as I read and re-read this parable this week is that I have played every role in this story. I have been the loyal soldier, performing my duties to please the commander. I have been the boss, deriving benefit from the labour of others. And I have been the defiant truth-teller, refusing to participate in the oppressive system.

The point of this parable, I think, was not to condemn or demonise any particular person. It was to publicly acknowledge the truth of the life of the Jewish people in the Roman Province of Palestina. And it was to propose another way. We do not have to participate in systems that disintegrate and destroy. We can opt out. We may be cast into the outer darkness where there is wailing and gnashing of teeth. What little we have may be taken away from us.

But we have choices, and our choices have power.

The Lord Be With You